Grasslands: A Climate Solution for Mongolia and the World

‘Grasslands’ has become a buzzword. It shows up in news reports, social media posts, and even during casual conversations. Yet, one essential point is often missing: grasslands are one of the world’s most impactful climate solutions.

So, what exactly are grasslands and how are they a climate solution?

The undervalued importance of grasslands

When asked about nature-based climate solutions, many imagine forests. Grasslands, in contrast, are often dismissed as empty, open land. In reality, they are among the planet's most crucial ecosystems.

As dynamic environments, grasslands are almost a real-life Zootopia. The diverse plants with varying heights growing in these ecosystems provide different niches for insects, birds, mammals, microbes, and other organisms, sustaining biodiversity across vast territories. In addition to biodiversity, they also play a foundational role in regulating water systems, supporting major rivers and wetlands.

A grassland is a terrestrial ecosystem dominated by grasses and grass-like plants with sparse shrubs and trees. On the other hand, rangelands, which are often used interchangeably with grasslands, is a sub-category that represents natural and semi-natural grasslands. The main distinguishing element of a rangeland is its function to serve as pasture for grazing livestock.

The importance of grasslands extends beyond these ecosystem services.

Grasslands are carbon storage hubs

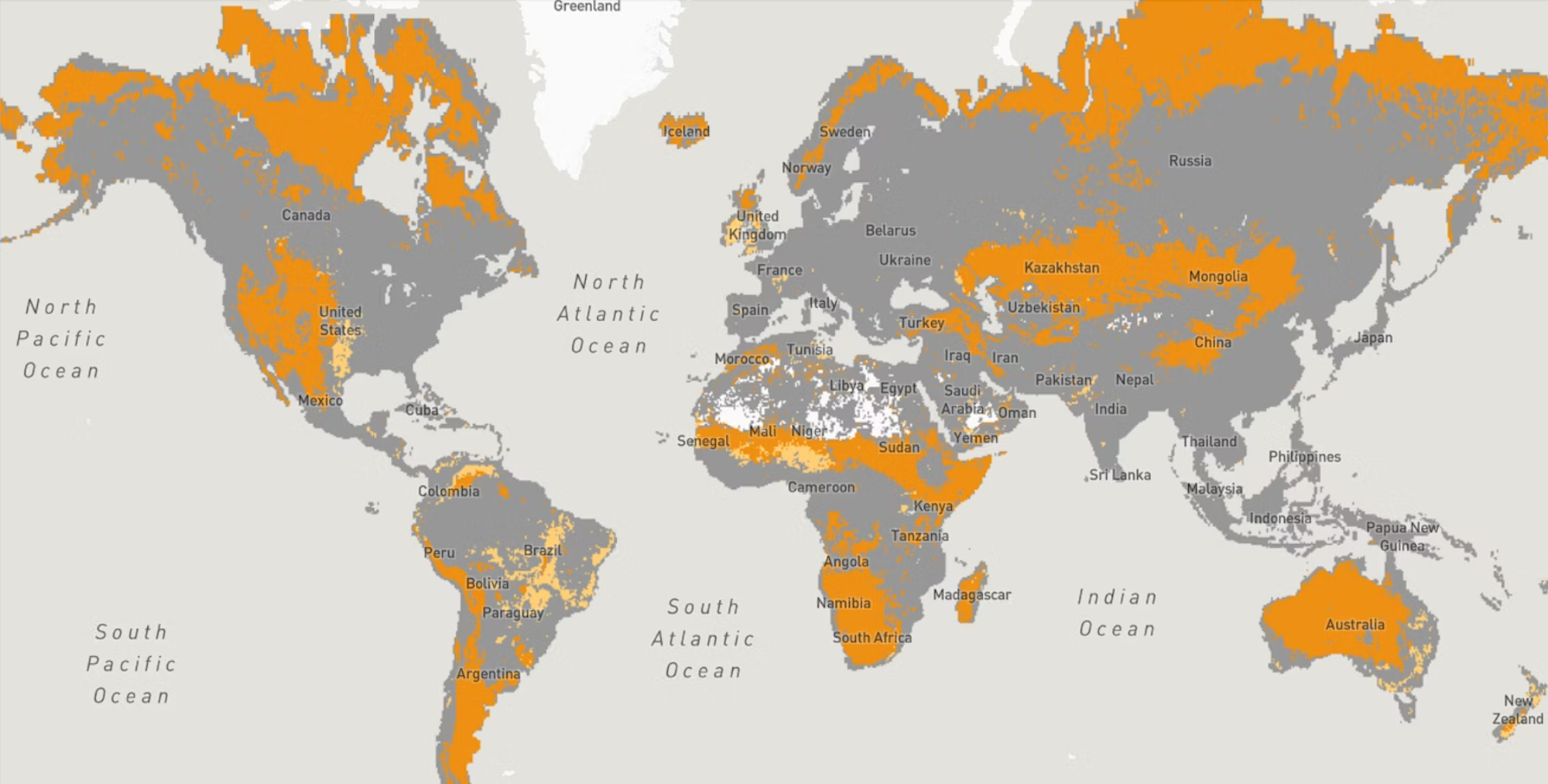

Covering nearly one third of the global land surface, these ecosystems store between 20 to 34 percent of the terrestrial carbon, which is three times more than tropical rainforests, according to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). While forests store carbon aboveground mostly in their woody biomass and leaves, grasslands store the majority of their carbon belowground through their deep, extensive root systems.

This belowground carbon storage makes grasslands more resilient to extreme events caused by climate change. A 2018 study by UC Davis found that grasslands in semi-arid regions are less vulnerable to wildfires, droughts and rising temperatures than forests. When forests burn, they can release decades of stored carbon. In contrast, grasslands lock the immense amount of carbon stored belowground in the soil even after disturbances. Therefore, “grasslands may be a more reliable carbon sink than forests.”

A carbon sink is a system that absorbs and stores more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than it emits, facilitating climate change mitigation. In contrast, a carbon source is a system that emits more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than it removes, contributing to climate change.

A global crisis: grasslands under pressure

Despite their importance, grasslands remain understudied and frequently misclassified. Weak regulatory frameworks make grasslands vulnerable to pressure from land-use change, overgrazing and climate stress. As a result, these ecosystems are experiencing rapid and extensive conversion and degradation. More than 50% of temperate and 16% of tropical grasslands have been already converted for agricultural and industrial uses.

This crisis does not only threaten wildlife but also the livelihoods of millions of people. According to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), over 100 million people globally depend on these ecosystems. In Mongolia, for example, approximately 300,000 semi-nomadic herders, who are among the last remaining nomadic pastoral communities in the world, rely on rangelands to sustain their livelihoods, as reported by the National Statistics Office.

Mongolia on the frontline of grassland degradation

Mongolia is a prime example of the global trend of accelerating grassland degradation. As reported by the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change (MECC), nearly 77% of Mongolia’s territory has been degraded, with desertification accelerating across the country. This widespread and intensive degradation threatens livestock health and productivity, herders’ livelihoods, our cultural heritage, ecosystem resilience, biodiversity, and soil carbon storage.

Two major forces are driving the degradation:

- Overgrazing: Mongolian herders manage over 60 million livestock, a number that far exceeds the nation’s ecological carrying capacity. Continuous pressure from grazing prevents rangeland from recovering and depletes soil nutrients.

- Climate change: Intensifying droughts, shifting precipitation patterns, and rising temperatures further degrade rangelands.

Together, these drivers create a self-reinforcing cycle of vegetation loss, soil degradation and ultimately, expansion of desertification.

The debate that delays action

Despite the intensity and urgency of the situation, researchers continue to debate whether climate change or overgrazing is the dominant driver of rangeland degradation. A study by Purevjav et al. highlights that climate change, rather than overgrazing, is primarily responsible for declining land productivity. While URECA’s recent research on grazing exclusion in Zavkhan Province suggests that overgrazing plays a significant role in degradation.

A drone image below from the latter study provides evidence, showing remarkable vegetation recovery after only three years of grazing exclusion. Both field observations and lab results revealed that removal of grazing pressure improved vegetation growth, promoted soil recovery, and enhanced carbon storage, when compared with the initial conditions.

Taken together, these findings support that both climate change and overgrazing are contributing to rangeland degradation. Although it is crucial to identify the dominant driver, waiting for scientific consensus only delays urgently needed actions. Thus, the debate should not divert policy attention, especially when the livelihoods of 300,000 herders depend on the rangelands.

Leveraging carbon potential of grasslands

In addition to providing climate mitigation and adaptation solutions, grasslands offer economic opportunity. By enhancing carbon sequestration through protection and restoration measures, grassland project developers can generate verified carbon credits. The credits can be traded in the global carbon markets and generate revenue to channel toward local restoration efforts and benefit-sharing mechanisms with local communities.

Around the world, communities, countries and organizations are increasingly restoring grasslands through community-based projects.

From neglect to global priority

Grasslands are finally receiving the attention they deserve. In 2020, WWF launched the Global Grasslands and Savannahs Dialogue Platform to elevate grasslands in global conservation and climate adaptation efforts. The initiative is promoting awareness, deepening our understanding of these ecosystems and channeling investments to protect, manage and restore them. This exemplary initiative highlights the change in global perception of grasslands: from neglect to priority.

Mongolia is likewise recognizing the significance of rangeland restoration. Set to host the 17th session of the Convention’s Conference of the Parties (COP17) in 2026, Mongolia will bring together 197 parties of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). Happening during the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists, the global forum will enable crucial discussions and decisions to accelerate action against desertification, drought, and land degradation.

Unlocking the full potential of grasslands

Protecting grasslands is no longer optional; it is an essential climate mitigation and adaptation opportunity. Restoration and sustainable management of grasslands will decelerate degradation, strengthen the livelihoods of local communities, protect and maintain biodiversity, and accelerate progress in achieving our climate goals. It is time to unlock the full potential of grasslands, the overlooked climate solution for Mongolia and the world.

Read about URECA’s contribution in the second article of this series.

Comments ()